We wanted to feature an excerpt from the blog Early Marietta which you can find a link to here. Be sure to check out new posts from us and Early Marietta regularly.

The campfire faded as the evening wore on, casting flickering shadows on the trees around the Indians’ camp. Two braves guarded the young boys captured from their home two days earlier. Lewis, the oldest at just 13 years of age, comforted his frightened younger brother Jacob while pretending to be asleep himself. He was barely at teenager, yet Lewis was frontier savvy, alert, and incredibly patient. Though wounded by a gunshot during their capture, he refused to let the Indians see his pain. He was livid at the Indians’ harsh treatment and taunts. They had to escape that night, he reckoned, to avoid death or torture.

For hours he waited, quietly muttering “Courage, courage.” At last their guards nodded off into deep slumber, and they slipped out of the camp. Lewis brazenly sneaked back to the camp twice to retrieve moccasins for them to wear and to take back his father’s musket and powder horn. They made it back to their family near Wheeling WV after several harrowing days.

The year was 1777. The oldest boy was Lewis Wetzel, who became a remarkable frontier fighter and scout. His frontier training began at an early age. Indians were a constant threat to the Lewis settlement on Wheeling Creek. Lewis’s father John Wetzel taught frontier skills to all of his seven children – sons and daughters. Lewis became proficient in shooting, use of knife and tomahawk, agility, endurance, and tracking.

The Wetzel legend – Indian killer, larger-than-life frontier fighter

He began a life-long campaign to hunt down and kill Indians. Pioneer families considered him a hero as their defenders against the Indian threat. Others regarded him as a sociopathic killer whose tactics amounted to atrocities against the Indians he hunted.

Dozens of books and treatises have been written about Lewis Wetzel. He appears as a character (or fictional characters inspired by him) in several books by writers such as Zane Grey, James Fennimore Cooper, and Allan Eckert. Anne Jennings Paris, a descendent of Wetzel, was inspired to write a series of poems about him in Killing George Washington: the American West in Five Voices.

The Zane Grey Frontier Trilogy: Betty Zane, The Last Trail, The Spirit Of The Border[Zane Grey] on Amazon.com. … They are a virtual narrative history of the Zane family,Lewis Wetzel, and frontier life and indian warfare in the Ohio river valley ..

Several places are named for Wetzel, including nearby Wetzel County WV. Yet despite the many accounts of his life going back to the mid-1800s, some truths about him remain elusive. Differing story versions, legend, and fictional depictions mingle with the actual facts to create the fascinating Lewis Wetzel historical figure.

Lewis Wetzel exploits

Stories of his exploits abound. The year after his escape from Indians he helped Forest Frazier rescue his wife Rose who was abducted by Indians. Lewis had skillfully tracked the Indians, found their camp, and waited all night to attack them as they awoke. They returned with Rose and four Indian scalps. The incident was the basis for the novel Forest Rose by Emerson Bennett published in the mid-1800s.

He was renowned for the ability to reload, prime, and shoot his musket while running at full speed. At age 16, he joined a group of settlers who were chasing Indians who had stolen their horses. The Indians initially fled, allowing the settlers to recover the horses. But the Indians soon reappeared. The settlers promptly abandoned the chase, leaving Lewis on his own. He faked being shot and when the Indians came to get his scalp, he shot one of them. He killed another while being chased and reloading on the run. Lewis returned to Wheeling Creek with two scalps, bragging to all who would listen.

In 1782, he and Thomas Mills were attacked by Indians while trying to retrieve Mills’ horse. Mills was mortally wounded by a volley of Indians’ gunfire. Lewis instantly fled at full speed, soon outrunning all but four Indians. One by one, he shot three of them after reloading on the run. One of those Indians had been close enough to grab the end of Lewis’s rifle as he tried to fire and pulled him down to the ground. The Indian taunted Lewis: “White man die….hurry up, chiefs, see Wetzel die.” This enraged Lewis who managed to thrust the rifle to the Indian’s neck and kill him. The fourth gave up the chase, exclaiming “no catch dat man, gun always loaded.”Illustration of the three Indian chase described above. From http://www.patc.us/history/native/wetzel.html.; content reprinted from History of the Early Settlement and Indian Wars of West Virginia (DeHass), 1851.

Wetzel’s personality: eccentric, friendly to some, a dark side.

He was a loner, living for long periods alone in the woods, often staying in hideouts such as rock outcroppings. One such location is in present day Lancaster, Ohio. Another was near Moss Run in Washington County, Ohio. When not in the woods he played the fiddle in taverns and excelled in shooting competitions. Wetzel was described as being friendly to dogs and children, but often aloof with adults. He never had a home, married, owned land, or held an ordinary job.

His appearance was distinctive. He is described as about six feet tall, raw boned, with a swarthy appearance, jet black eyes, pock-marked face from small pox, braided hair which reached to his calves when combed out, and pierced ears from which he wore silk tassels. Some said he had the skin color of Indians.

Imagined portrait of Wetzel from glenbarnesart.com, based on historical descriptions and appearance of descendents.

His dark side was the obsession with hunting and killing Indians, “often for sport”, “stalking them like prey”, some said. He often tracked small hunting parties for long periods, then attacked – killing them, taking scalps, and fighting his way out if there were survivors. Lewis claimed that he had scalps of 27 Indians that he killed between 1777 and 1788. Other sources put the figure at 100 or more.

Indians called him “Deathwind.” He seemed fearless. He and scout Samuel Brady even walked into Indian camps along the Sandusky River disguised as Indians to ascertain their strength. Twice he killed Indian chiefs who were part of peace negotiations. Some historians have described him as “remorseless,” “a terrorist,” and a “cultural embarrassment.”

Marietta area connections

Lewis Wetzel had connections to the Marietta area. He often hunted wild game – and Indians – in the area. According to local lore, he frequented a rock outcropping near Moss Run in Washington County identified as “Wetzel’s Cave.”

Lewis was friends with Hamilton Kerr, later a scout and hunter for the Marietta settlement, when he lived in the Wheeling area. They often hunted and trapped together, though Kerr did not share Wetzel’s fanaticism in killing Indians. A Hamilton Kerr decendent was told that Hamilton later avoided the Wetzels because though brave, “they were rash men who subjected themselves and their companions to danger.”

One particular hunting trip brought Kerr, Lewis, and other members of Lewis’s family downriver near the Muskingum River in 1784. They camped on the island that would later be Hamilton Kerr’s home. They set traps for beaver, posted watches for Indians, and went to sleep. The next morning, the traps were gone. Indians! Sensing danger, they began paddling up the Ohio River to get away. Indians appeared and opened fire near Duck Creek. Lewis’s brother George Wetzel and Kerr’s dog died. Hamilton Kerr was wounded. One account states that Lewis’s father John was also in the party and died.

Lewis was not wounded (this was typical; his luck or knack for avoiding capture or injury was legendary) and paddled furiously out of danger and stopped near Long Reach. They buried the dead, apparently using only their paddles. Upon returning to Wheeling, Hamilton was nursed back to health by Rebecca Williams, known for her frontier medical skills. Isaac and Rebecca Williams would move to the Virginia shore opposite the Muskingum River, site of the current Williamstown, in 1787.

Lewis Wetzel was in the Marietta area in 1788. Reportedly he served as a hunter to supply wild game for the new settlement and was a part time scout at Fort Harmar. In 1789 (some accounts date the event in 1791) he shot a Seneca Chief named Tegunteh, nicknamed George Washington because of his exemplary character, as he approached Fort Harmar for treaty negotiations being overseen by General Josiah Harmar.

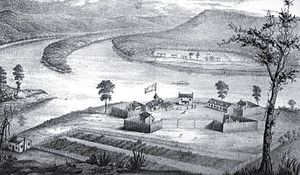

Fort Harmar near Marietta by Joseph Gilman. Note Treaty house for Indian negotiations at bottom left of image.

Harmar was outraged at this wanton killing and issued a warrant to arrest Wetzel for the murder of Tegunteh. Harmar later wrote to Secretary of War Henry Knox:

This George Washington (Tegunteh) is a trusty confidential Indian…. He is well known to Governor St. Clair, and I believe there is not a better Indian to be found. The villain who wounded him I am informed is one Lewis Whitzell. I am in hopes to be able to apprehend him and deliver him to Judge Parsons to be delt with; but would much rather have it in my power to order such vagabonds hanged up immediately without trial.

The first effort to capture Wetzel at Mingo Bottom was thwarted by armed locals who considered Wetzel a hero as their protector against Indians. The outnumbered soldiers wisely backed off. He was later captured at the home of Hamilton Kerr on Kerr’s Island and imprisoned at Fort Harmar.

He brazenly escaped from Fort Harmar by cajoling his guards to give him more freedom to move around inside the Fort. While darting around “for exercise”, he leaped over the wall of the Fort before his surprised guards could react. His pursuers assumed he would run as far away as possible. Lewis stymied them by hiding in plain sight – under a log, right along a trail, not far from the Fort. Soldiers and Indians, each hunting for him, moved back and forth over his log, even standing at one point atop the log. After three days, he emerged from the log and crossed the Ohio River, still shackled, to a friend’s place in Virginia. A friendly blacksmith removed the shackles, and he was a free spirit once more – for a while.

He was captured a second time after a soldier spotted him in a tavern at present day Maysville, KY. He was taken to Fort Washington near Cincinnati. Once again, armed supporters came to his rescue. More than 200 settlers threatened to free Lewis by force if he was not released. Territorial Judge John Symmes finally released Lewis on a writ of habeas corpus – and never recalled him for trial.

Later years

He left the Ohio Valley area in the 1790s. The Treaty of Greenville in 1795 ended the menace of Indian attacks in the Ohio area. Wetzel’s star as an Indian fighting hero faded. Less is known of his later activities. His name is recorded as a resident in Spanish New Orleans. It is reported that he did jail time for counterfeiting, romanced a Spanish official’s wife, and joined the Louis and Clark expedition. The latter two activities are not documented. Historian Ray Swick reported a surprising recent discovery about Wetzel in an article authored with Brian D. Hardison. Hardison obtained a document at auction in 2007 which lists Lewis Wetzel as a participant in the ill-fated Aaron Burr expedition. There are no details on his role.

He died in 1808 and was buried near a cousin’s home in Mississippi. A researcher found and relocated his remains in 1942. He is now buried next to his older brother Martin Wetzel in McCreary Cemetery near Moundsville, WV, just two miles from the Wetzel family homestead. Though long departed, his reputation lives on.